Apple has now filed a normal appeal, after being turned down for en banc review by the entire Federal Circuit, regarding Judge Lucy Koh's refusal to order an injunction against Samsung in the first Apple v. Samsung case, no. 11-CV-1846. That's the one where Apple got a jury to order a billion plus in damages. Although I doubt that figure will stand. Anyway, Apple wants an injunction too, and here's the brief [PDF] asking for it. The order [PDF] it's appealing is found

here as text. And I'll work on a text version for you of this appeal brief next.

Meanwhile, here's a taste, the issue as Apple sees it and the Introduction:STATEMENT OF ISSUE

Whether the district court abused its discretion in denying Apple’s motion for a permanent injunction.

INTRODUCTION

Apple brought this lawsuit to halt Samsung’s deliberate copying of Apple’s innovative iPhone and iPad products. After a jury found that Samsung infringed numerous Apple patents and diluted Apple’s protected trade dress, Apple sought a permanent injunction. Apple proved to the district court’s satisfaction that: (1) “Apple has continued to lose market share to Samsung,” which “can support a finding of irreparable harm” (A5); (2) Samsung’s actions took market share from Apple with respect to not only smartphones and tablets, but also substantial downstream sales of other products, such that Apple “may not be fully compensated by the damages award” (A16); (3) Samsung’s arguments concerning the balance of hardships were unavailing because Samsung claimed to have stopped selling or to have developed design-arounds for the infringing products and “cannot now turn around and claim that [it] will be burdened by an injunction that prevents sale of these same products” (A18-19); and (4) “the public interest does favor the enforcement of patent rights” (A20).

Under eBay Inc. v. MercExchange, L.L.C., 547 U.S. 388 (2006), these findings should have led to a permanent injunction against Apple’s adjudicated infringing competitor. Nevertheless, the district court denied relief because it believed that Apple was required to show “not just that there is demand for the patented features” connecting Apple’s irreparable harm to Samsung’s infringement, “but that the patented features are important drivers of consumer demand for the infringing products.” A12. The district court stated that, “[w]ithout a causal nexus, [the court] cannot conclude that the irreparable harm supports entry of an injunction.” Id.

This additional “causal nexus” requirement—particularly when applied as rigidly as the district court did here—is contrary to the Supreme Court’s and this Court’s permanent injunction precedents. Unless corrected, the district court’s

ruling that a strong showing on the four eBay factors is defeated by a supposed lack of “causal nexus” will create a bright-line rule that precludes injunctive relief even “in traditional cases, such as this, where the patentee and adjudged infringer both practice the patented technology.” Robert Bosch LLC v. Pylon Mfg. Corp., 659 F.3d 1142, 1150 (Fed. Cir. 2011). This Court should correct that course by reversing the district court’s order.

Apple repeatedly calls Samsung's infringement willful. But the judge on the case ruled that this was not the case regarding the patents. Samsung had the belief that Apple's patents were invalid, due to prior art. The jury found willfulness regarding trade dress, but Judge Koh wrote that Apple had not "not clearly shown how it has in fact been undercompensated for the losses it has suffered due to Samsung’s dilution of its trade dress." A billion plus dollars ought to cover that. Apple, though, says it lost business, and it wants to prevent future loss. Plus, the judge believed that Apple could license the patents going forward, but Apple asserts that it never would license its design patents to Samsung, has rarely licensed them to anyone, and even its utility patents it wouldn't want to licnese to Samsung without limitations. So it believes the judge erred in believing that mere money could make Apple whole. It doesn't wish to license those design patents to Samsung, not for love or money. And it has never licensed its trade dress to anyone and doesn't want to:

The unrestricted compulsory license to Apple's patents that

Samsung would enjoy absent an injunction is entirely inconsistent with Apple's

"rare" and limited licensing practice for patents covering its unique user

experience.

Nor was the district court correct to conclude that licenses of certain Apple

utility patents to IBM, Nokia, and HTC suggested Apple's willingness to license

its asserted patents to Samsung for use in competing products. Those agreements

provide no basis for concluding that Apple would ever be willing to license its

design patents to Samsung. Indeed, Apple's licenses to IBM, Nokia, and HTC do

not even include any such design patents. A4308(¶1.10) (Nokia license limiting

"Licensed Apple Patents" to certain specific utility patents and patents essential to

comply with industry standards); A4443 (IBM license excluding all Apple design

patents except for fonts); A4783(¶1.11) (HTC license excluding Apple's design

patents from "Covered Patents").

The IBM, Nokia, and HTC licenses also do not suggest any willingness on

Apple's part to license its asserted utility patents--without restriction--to a direct

competitor like Samsung. This is, in my view, Apple's strongest argument. But this is what is driving Apple:A permanent injunction is the only way to vindicate the property rights that Congress and the Patent Office conferred on Apple against the adjudicated trespass by its direct competitor. Vindication is a hard thing to try for in a court of law. I used to work for a lawyer who would never take a client that mentioned wanting it. Because it's an unrealistic goal, most of the time. Money is what court's can give you. And Apple got that at the trial. Vindication is another beast altogether. The problem for Apple is that it's asking the court to put an injunction in place against products that Samsung no longer sells in the US or for which it has come up with workarounds. Here's how Apple answers that: At the same time, Samsung's claim that it has discontinued sales of its

infringing products or designed around Apple's patents in no way diminishes

Apple's need for injunctive relief. Because Samsung frequently brings new

products to market (A20880-20881(880:13-881:7); A23037(3037:2-4)), an

injunction is essential to providing Apple the swift relief needed to combat any

future infringement by Samsung through products not more than colorably

different from those already found to infringe. Apple should not have to bear the

risk that Samsung's supposed design-arounds are insufficient or that Samsung will

not again resume its infringement.

Absent a permanent injunction, Apple would be significantly harmed by the

risk of Samsung's continued infringement. First, the parties have product lines of

vastly different scope. Unlike Apple, which launches only a small number of new

products each year and sells only two or three smartphone products at any given

time, Samsung launches 50 new smartphones each year and has over 100 products

available in the United States at any given time. A20880-20881(880:13-881:7);

A23037(3037:2-4) ("Samsung currently has 103 models in the United States.

They come out with more than one a week."). Even if the infringing products at

issue here were enjoined, Samsung would still have numerous products on the

market. By contrast, Apple's much narrower product line must compete with any

ongoing infringement by Samsung, which as explained above (pp. 17-19) has

already cost Apple significant market share. It wants an injunction just in case?

Causal nexus means that people are buying your product because they want the patented feature, and Judge Koh wrote about Apple's design patents this:

However, Apple’s evidence does not establish that any of Apple’s three design patents covers a particular feature that actually drives consumer demand. ...First, though more specific than the general “design” allegations, they are still not specific enough to clearly identify actual patented designs. Instead, they refer to such isolated characteristics as glossiness, reinforced glass, black color, metal edges, and reflective screen. Id. Apple does not have a patent on, for example, glossiness, or on black color. And then on the rest, the utility patents, she ruled:

The phones at issue in this case contain a broad range of features, only a small fraction of which are covered by Apple’s patents. Though Apple does have some interest in retaining certain features as exclusive to Apple, it does not follow that entire products must be forever banned from the market because they incorporate, among their myriad features, a few narrow protected functions. Especially given the lack of causal nexus, the fact that none of the patented features is core to the functionality of the accused products makes an injunction particularly inappropriate here....

Weighing all of the factors, the Court concludes that the principles of equity do not support the issuance of an injunction here. First and most importantly, Apple has not been able to link the harms it has suffered to Samsung’s infringement of any of Apple’s six utility and design patents that the jury found infringed by Samsung products in this case. It wouldn't be in the public interest, she ruled, to ban entire products due to some minor infringing features nobody even is looking for when buying the products particularly when there are so many other features that are not infringing that the public wants to buy:

It would not be equitable to deprive consumers of Samsung’s infringing phones when, as explained above, only limited features of the phones have been found to infringe any of Apple’s intellectual property. Though the phones do contain infringing features, they contain a far greater number of non-infringing features to which consumers would no longer have access if this Court were to issue an injunction. The public interest does not support removing phones from the market when the infringing components constitute such limited parts of complex, multi-featured products. Apple on the other hand argues that people really do buy their products for their design.

Update: If you thought Oracle had a lot of lawyers for its appeal, wait until you see how many Apple has on board. 62 lawyers are listed. Twenty from Morrison & Foerster, 34 from Wilmer Cutler, 3 from Taylor, 3 from Cooley, and 2 from Bridges. So. Much. Money. Out. The. Window. And you know what happens when you have that many lawyers? They think up more ways to try tricky, inventive new ways to try to get you what you want. Even if you shouldn't want it. Even when you could be spending that money on innovative new products. Because that is what lawyers do. They are wired to try to win. So they tell you to keep going. Just a little bit more and victory will be yours.

Sigh. Sadly Apple doesn't listen to me. But it breaks my heart, to tell you the truth, to see this happening. Count them for yourselves. I'm cross-eyed from doing the text, and I might have missed one or double counted one. Does it matter? It's too many lawyers in any rational system. Here's what Apple wants. An injunction against Samsung. It doesn't like the causal nexus requirement, but if the panel agrees with the district court, Apple wants an en banc review by the entire court. Yes. Still on that. And why wait to ask the way you normally do, after you lose? Maybe to let the panel know that Apple isn't going to be satisfied with their decision unless it matches what Apple wants.

Update 2: Matt Rizzolo at The Essential Patent Blog highlights an interesting subplot: Because the causal nexus requirement cited by the district court came in two Federal Circuit cases evaluating preliminary injunctions, Apple presents an interesting argument where it stresses the difference between preliminary and permanent injunctions. Apple argues that courts have greater latitude and discretion in tailoring permanent injunctions, in order to better balance the patentee’s right to exclude with the injunction’s effect on the infringer (and the public). Thus, according to Apple, there’s less (or no) need to show a causal nexus for permanent injunctions — according to Apple, it’s never been required by the Federal Circuit or Supreme Court. Given that both of these courts have applied basically the same standard for issuing preliminary and permanent injunctions (aside from the requirement of a likelihood of success on the merits for preliminary injunctions), however, this may be an uphill battle. But Apple could have a better chance with its fallback arguments that it did in fact satisfy the causal nexus requirement, particularly for its design patents (and this has the added bonus for the Federal Circuit of continuing to be able to hold patentees to the higher causal nexus standard in the future).

When Samsung responds, we can expect it to say that the causal nexus requirement is nothing new, even for permanent injunctions, and that of course Apple would need to show a link between infringement and irreparable harm — if using the infringing feature or design isn’t irreparably harming Apple, it makes no more sense to enjoin Samsung from implementing these features than it does to prevent Samsung from running commercials or locating an office in California. In Samsung’s eyes, it would all be the same — without some connection, there’s no cause and effect justifying an injunction.

It will be very interesting to see how the Federal Circuit comes out here, both substantively and procedurally. Apple has urged the court to take the case up en banc if necessary, which the court may do in order to provide some clarity regarding the causal nexus requirement. Lastly, let’s tie this back to the blog. If the causal nexus requirement stands, it will be very difficult for standard-essential patent owners — even if they have never promised to license their SEPs on RAND terms — to ever be able to get an injunction in U.S. courts.

Here it is as text:

*******************

2013-1129

___________________

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FEDERAL CIRCUIT

APPLE INC.,

Plaintiff-Appellant,

v.

SAMSUNG ELECTRONICS CO., LTD.,

SAMSUNG ELECTRONICS AMERICA, INC., and

SAMSUNG TELECOMMUNICATIONS AMERICA, LLC,

Defendants-Appellees.

_________________

Appeal from the United States District Court for the

Northern District of California in case no. 11-CV-1846, Judge Lucy H. Koh.

_____________

BRIEF FOR PLAINTIFF-APPELLANT APPLE INC.

_______________

MICHAEL A. JACOBS

RACHEL KREVANS

ERIK J. OLSON

RICHARD S.J. HUNG

GRANT L. KIM

MORRISON & FOERSTER LLP

[address, phone]

WILLIAM F. LEE

MARK C. FLEMING

JOSEPH J. MUELLER

LAUREN B. FLETCHER

WILMER CUTLER PICKERING

HALE AND DORR LLP

[address, phone]

JONATHAN G. CEDARBAUM

WILMER CUTLER PICKERING

HALE AND DORR LLP

[address, phone]

Counsel for Plaintiff-Appellant Apple Inc.

February 12, 2013

CERTIFICATE OF INTEREST

Pursuant to Federal Circuit Rule 47.4, counsel of record for Plaintiff-

Appellant Apple Inc. certifies as follows:

1. The full name of every party represented by us is:

Apple Inc.

2. The names of the real parties in interest represented by us are:

Not applicable

3. All parent corporations and any publicly held companies that own 10

percent or more of the stock of the parties represented by us are:

None.

4. The names of all law firms and the partners or associates that

appeared for the parties represented by us in the trial court, or are expected to

appear in this Court, are:

Morrison & Foerster LLP:

| Deok K.M. Ahn | Harold J. McElhinny |

| Jason R. Bartlett | Andrew E. Monach |

| Charles S. Barquist | Erik J. Olson |

| Francis Chung-Hoi Ho | Taryn Spelliscy Rawson |

| Richard S.J. Hung | Christopher Leonard Robinson |

| Michael A. Jacobs | Jennifer L. Taylor |

| Esther Kim | Alison M. Tucher |

| Grant L. Kim | Patrick J. Zhang |

| Rachel Krevans | Nathan Brian Sabri |

| Marc J. Pernick | Ruchika Agrawal |

i

Wilmer Cutler Pickering Hale and Dorr LLP:

| David B. Bassett | William F. Lee |

| James C. Burling | Andrew L. Liao |

| Jonathan G. Cedarbaum | Leah Litman |

| Robert D. Cultice | Joseph J. Mueller |

| Andrew J. Danford | Michael Saji |

| Michael A. Diener | Brian Seeve |

| Christine E. Duh | Mark D. Selwyn |

| Mark D. Flanagan | Ali H. Shah |

| Mark C. Fleming | Victor F. Souto |

| Lauren B. Fletcher | James L. Quarles III |

| Richard Goldenberg | Timothy D. Syrett |

| Robert J. Gunther, Jr. | Robert Tannenbaum |

| Liv L. Herriot | Louis W. Tompros |

| Michael R. Heyison | Samuel Calvin Walden |

| Peter J. Kolovos | Rachel L. Weiner |

| Derek Lam | Emily R. Whelan |

| Brian Larivee | Jeremy Winer |

Taylor & Company Law Offices LLP:

Joshua Ryan Benson

Stephen E. Taylor

Stephen M. Bundy

Cooley LLP:

Benjamin George Damstedt

Timothy S. Teter

Jesse L. Dyer

ii

Bridges & Mavrakakis LLP:

Kenneth H. Bridges

Michael T. Pieja

Dated: February 12, 2013

Respectfully submitted,

/s/ William F. Lee

WILLIAM F. LEE

WILMER CUTLER PICKERING

HALE AND DORR LLP

[address, phone]

Attorney for Plaintiff-Appellant Apple Inc.

iii

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

CERTIFICATE OF INTEREST ..........................................i

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES .......................................... vii

STATEMENT OF RELATED CASES ................................... 1

JURISDICTIONAL STATEMENT ..................................... 2

STATEMENT OF ISSUE....................................... 2

INTRODUCTION ................................................ 2

STATEMENT OF CASE ........................................... 4

STATEMENT OF FACTS ........................................ 5

A. Apple's iPhone And iPad Are Revolutionary Products Whose

Success Is Built On Their Unique Design And User Experience ......... 5

1. Apple's design patents and iPhone trade dress ........................... 7

2. Apple's utility patents ....................................... 10

B. Samsung Deliberately Copied Apple's iPhone And iPad To

Compete Directly With Apple.............................................. 12

C. Through Its Infringement And Dilution, Samsung Took

Significant Market Share From Apple ..................................... 17

D. Apple Lost Substantial Downstream Sales Due To Samsung's

Infringement And Dilution .............................................. 19

E. Design And Ease Of Use Are Important To Smartphone

Purchasers ............................. 20

F. The District Court's Decision .............................. 23

iv

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT ......................................... 27

STANDARD OF REVIEW ................................... 29

ARGUMENT .............................................. 29

I. THE EQUITIES STRONGLY FAVOR GRANTING INJUNCTIVE RELIEF TO BAR

FURTHER PATENT INFRINGEMENT BY A DIRECT COMPETITOR....................... 30

A. Apple Is Being Irreparably Harmed By The Threat Of Its Direct

Competitor's Continued Infringement ..................................... 32

1. Apple and Samsung compete directly for first-time

smartphone buyers ............................... 32

2. Apple has lost market share due to its direct competitor's

adjudicated infringement ........................................ 33

3. Apple has lost downstream sales due to its direct

competitor's adjudicated infringement .............................. 34

B. Money Damages Are Inadequate To Remedy Apple's Loss Of

Market Share And Downstream Sales To Its Direct Competitor ....... 36

C. The Balance Of Hardships Strongly Favors Enjoining Further

Infringement From Apple's Direct Competitor .................................. 41

D. An Injunction Would Promote The Public Interest In Patent

Enforcement Against A Direct Competitor.................................. 44

II. THE DISTRICT COURT ERRONEOUSLY DENIED APPLE A PERMANENT

INJUNCTION DUE TO AN ALLEGED LACK OF A CAUSAL NEXUS .................... 47

A. The District Court's Adoption Of A Causal Nexus Requirement

In The Permanent Injunction Context Is Contrary To The Patent

Act And The Decisions Of The Supreme Court And This Court ....... 48

B. Importing A Causal Nexus Requirement For Preliminary

Injunctions Into The Permanent Injunction Context Is Unjustified

And Unnecessary ........................................... 51

v

C. The District Court's Rigid Application Of The Causal Nexus

Requirement Is Contrary To Principles Of Equity.............................. 59

D. In The Alternative, Any Reasonable Causal Nexus Requirement

Is Satisfied By Apple's Evidence That Product Design And User

Interface Are Important To Consumers .................................. 61

1. The patented designs drive consumer demand ......................... 62

2. The patented user interface features are important drivers

of consumer demand ......................................... 64

E. If The Panel Believes That Apple I And Apple IIPrevent

Reversal, Hearing En Banc Is Appropriate .............................. 66

III. THE DISTRICT COURT ERRONEOUSLY DENIED APPLE AN INJUNCTION

AGAINST SAMSUNG'S TRADE DRESS DILUTION................................. 68

CONCLUSION ................................ 71

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

CERTIFICATE OF COMPLIANCE

vi

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Page(s)

CASES

Abbott Laboratories v. Sandoz, Inc.,

544 F.3d 1341 (Fed. Cir. 2008) .......................................... 44

ActiveVideo Networks, Inc. v. Verizon Communications, Inc.,

694 F.3d 1312 (Fed. Cir. 2012) ................................. 37, 48, 52

Acumed LLC v. Stryker Corp.,

551 F.3d 1323 (Fed. Cir. 2008) ................................. 31, 34, 36, 37, 40, 45, 50

Allee v. Medrano,

416 U.S. 802 (1974) ............................................... 69

Apple, Inc. v. Samsung Electronics Co.,

678 F.3d 1314 (Fed. Cir. 2012) ............................. 1, 26, 27, 31, 37, 60, 61

Apple Inc. v. Samsung Electronics Co.,

695 F.3d 1370 (Fed. Cir. 2012) ........................................passim

Broadcom Corp. v. Qualcomm Inc.,

543 F.3d 683 (Fed. Cir. 2008) ................................. 35, 36, 37, 40, 49, 50, 51, 57

eBay Inc. v. MercExchange, L.L.C.,

547 U.S. 388 (2006) .......................................passim

Edwards Lifesciences AG v. CoreValve, Inc.,

699 F.3d 1305 (Fed. Cir. 2012) .............................. 52, 67

Garretson v. Clark,

111 U.S. 120 (1884) ........................................ 58

Grupo Mexicano de Desarrollo S.A. v. Alliance Bond Fund, Inc.,

527 U.S. 308 (1999) ..................................... 51

Gucci America, Inc. v. Guess?, Inc.,

868 F. Supp. 2d 207 (S.D.N.Y. 2012).............................. 69

vii

i4i Ltd. Partnership v. Microsoft Corp.,

598 F.3d 831 (Fed. Cir. 2010) ........................... 36, 44, 48, 53

International Rectifier Corp. v. IXYS Corp.,

383 F.3d 1312 (Fed. Cir. 2004) .............................. 46

Jeneric/Pentron, Inc. v. Dillon Co.,

205 F.3d 1377 (Fed. Cir. 2000) ................................ 53

Kewanee Oil Co. v. Bicron Corp.,

415 U.S. 470 (1974) ............................................ 44

LaserDynamics, Inc. v. Quanta Computer, Inc.,

694 F.3d 51 (Fed. Cir. 2012) ................................ 40, 58, 59

Lucent Technologies, Inc. v. Gateway, Inc.,

580 F.3d 1301 (Fed. Cir. 2009) ..................................... 58

Merial Ltd. v. Cipla Ltd.,

681 F.3d 1283 (Fed. Cir. 2012) ........................ 34

Momenta Pharmaceuticals, Inc. v. Amphastar Pharmaceuticals, Inc.,

686 F.3d 1348 (Fed. Cir. 2012) ........................ 52

O2 Micro International Ltd. v. Beyond Innovation Technology Co.,

No. 2011-1054, 2011 WL 5601460 (Fed. Cir. Nov. 18, 2011)

(nonprecedential).................................... 39, 40

OBH, Inc. v. Spotlight Magazine, Inc.,

86 F. Supp. 2d 176 (W.D.N.Y. 2000) ................................... 69

Polo Fashions, Inc. v. Dick Bruhn, Inc.,

793 F.2d 1132 (9th Cir. 1986) ............................. 69

Presidio Components, Inc. v. American Technical Ceramics Corp.,

702 F.3d 1351 (Fed. Cir. 2012) ........................ 31, 34, 48, 59

Robert Bosch LLC v. Pylon Manufacturing Corp.,

659 F.3d 1142 (Fed. Cir. 2011) ........................passim

viii

Sanofi-Synthelabo v. Apotex, Inc.,

470 F.3d 1368 (Fed. Cir. 2006) ........................... 25, 31, 44

TiVo Inc. v. EchoStar Corp.,

646 F.3d 869 (Fed. Cir. 2011) (en banc) .............................. 46

Uniloc USA, Inc. v. Microsoft Corp.,

632 F.3d 1292 (Fed. Cir. 2011) ................................... 58

Verizon Services Corp. v. Vonage Holding Corp.,

503 F.3d 1295 (Fed. Cir. 2007) .................................. 31, 35, 57

Voda v. Cordis Corp.,

536 F.3d 1311 (Fed. Cir. 2008) ...................................... 37

Warner Chilcott Labs Ireland Ltd. v. Mylan Pharmaceuticals Inc.,

451 F. App'x 935 (Fed. Cir. 2011) .................................. 51

Whitserve, LLC v. Computer Packages, Inc.,

694 F.3d 10 (Fed. Cir. 2012) ............................... 53

Winter v. Natural Resources Defense Council, Inc.,

555 U.S. 7 (2008) ...................................... 51

STATUTES

15 U.S.C.

§ 1121 ................................................... 2

§ 1125 ............................................... 68, 69, 70

28 U.S.C.

§ 1292 .................................................2, 5

§ 1331 ................................................. 2

§ 1338............................................. 2

§ 1367................................................. 2

35 U.S.C.

§ 154 ................................................. 52

§ 283 ................................................. 48

ix

OTHER AUTHORITIES

Shaver, Illuminating Innovation, 69 Wash. & Lee L. Rev. 1891 (1943) ................... 56

x

STATEMENT OF RELATED CASES

This appeal arises from the district court's order denying Apple a permanent

injunction following a jury's verdict that Samsung infringed six Apple patents and

diluted Apple's iPhone trade dress. A1-23. Most post-verdict motions have been

resolved, but Samsung's motion for a new trial on damages remains pending

before the district court. Final judgment has not yet been entered.

This Court previously resolved an appeal in this case arising from the district

court's denial of Apple's motion for a preliminary injunction. Apple, Inc. v.

Samsung Elecs. Co., No. 2012-1105, 678 F.3d 1314 (Fed. Cir. May 14, 2012)

(Bryson, J., joined by Prost, J.; opinion concurring in part and dissenting in part by

O'Malley, J.), pet. for reh'g denied (June 19, 2012). On remand from that appeal,

the district court entered a preliminary injunction from which Samsung appealed

(No. 12-1506). That appeal was voluntarily dismissed after the jury's verdict.

This Court previously resolved an appeal in a separate case involving the

same parties and some of the same accused products arising from the district

court's grant of Apple's motion for a preliminary injunction. Apple Inc. v.

Samsung Elecs. Co., No. 2012-1507, 695 F.3d 1370 (Fed. Cir. Oct. 11, 2012)

(Prost, J., joined by Moore & Reyna, JJ.), pet. for reh'g denied (Jan. 31, 2013).

Apple and Samsung have also appealed from several collateral orders in this

case in which the district court denied Apple's and Samsung's requests to seal

-1-

certain confidential record material. Apple Inc. v. Samsung Elecs. Co., Nos. 2012-1600, 2012-1606, 2013-1146 (Fed. Cir.). This Court has scheduled argument in

those appeals for March 26, 2013.

On January 16, 2013, Apple filed a petition for initial hearing en banc in this

appeal, which was denied on February 4, 2013.

JURISDICTIONAL STATEMENT

The district court had jurisdiction under 15 U.S.C. § 1121 and 28 U.S.C.

§§ 1331, 1338, and 1367. The district court denied Apple's motion for a

permanent injunction on December 17, 2012, and Apple timely appealed. A4923.

This Court has jurisdiction under 28 U.S.C. § 1292(c)(1).

STATEMENT OF ISSUE

Whether the district court abused its discretion in denying Apple's motion

for a permanent injunction.

INTRODUCTION

Apple brought this lawsuit to halt Samsung's deliberate copying of Apple's

innovative iPhone and iPad products. After a jury found that Samsung infringed

numerous Apple patents and diluted Apple's protected trade dress, Apple sought a

permanent injunction. Apple proved to the district court's satisfaction that: (1)

"Apple has continued to lose market share to Samsung," which "can support a

finding of irreparable harm" (A5); (2) Samsung's actions took market share from

-2-

Apple with respect to not only smartphones and tablets, but also substantial

downstream sales of other products, such that Apple "may not be fully

compensated by the damages award" (A16); (3) Samsung's arguments concerning

the balance of hardships were unavailing because Samsung claimed to have

stopped selling or to have developed design-arounds for the infringing products

and "cannot now turn around and claim that [it] will be burdened by an injunction

that prevents sale of these same products" (A18-19); and (4) "the public interest

does favor the enforcement of patent rights" (A20).

Under eBay Inc. v. MercExchange, L.L.C., 547 U.S. 388 (2006), these

findings should have led to a permanent injunction against Apple's adjudicated

infringing competitor. Nevertheless, the district court denied relief because it

believed that Apple was required to show "not just that there is demand for the

patented features" connecting Apple's irreparable harm to Samsung's

infringement, "but that the patented features are important drivers of consumer

demand for the infringing products." A12. The district court stated that,

"[w]ithout a causal nexus, [the court] cannot conclude that the irreparable harm

supports entry of an injunction." Id.

This additional "causal nexus" requirement--particularly when applied as

rigidly as the district court did here--is contrary to the Supreme Court's and this

Court's permanent injunction precedents. Unless corrected, the district court's

-3-

ruling that a strong showing on the four eBay factors is defeated by a supposed

lack of "causal nexus" will create a bright-line rule that precludes injunctive relief

even "in traditional cases, such as this, where the patentee and adjudged infringer

both practice the patented technology." Robert Bosch LLC v. Pylon Mfg. Corp.,

659 F.3d 1142, 1150 (Fed. Cir. 2011). This Court should correct that course by

reversing the district court's order.

STATEMENT OF CASE

After a three-week trial, a jury found that twenty-six Samsung smartphone

and tablet computer products infringed one or more of six Apple patents (A4186-

4192), that Samsung infringed five of the patents willfully (A4193), and that none

of Apple's asserted patents is invalid (id.). The jury also found that Samsung

willfully diluted Apple's iPhone trade dress through sales of six Samsung

smartphones. A4195-4196; A4198. The jury rejected all of Samsung's

infringement counterclaims (A4201-4204) and awarded Apple more than $1 billion

in damages (A4199).

Following the verdict, Apple moved for a permanent injunction prohibiting

Samsung from continuing to infringe Apple's patents and dilute Apple's trade

dress--whether through the twenty-six adjudicated infringing products or products

not more than colorably different from them. A4218-4219; A4251-4252. On

December 17, 2012, the district court denied Apple's motion for a permanent

-4-

injunction. A1-23. On December 20, 2012, Apple timely appealed from that order

pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 1292. A4923.

On January 29, 2013, the district court decided several of the parties' post-

trial motions. The court did not disturb the jury's finding that Samsung's

infringement satisfied the subjective prong of willful infringement, but concluded

that the objective prong was not satisfied and granted judgment as a matter of law

("JMOL") that Samsung's infringement was not willful on that basis. A116-122.

The district court otherwise denied Samsung's motion for JMOL, concluding that

the jury reasonably found that Apple's patents were infringed and not invalid and

that Apple's iPhone trade dress was protectable and willfully diluted.

A92-116.1

Samsung's motion for a new trial on damages remains pending. Final judgment

has not yet entered.

STATEMENT OF FACTS

A. Apple's iPhone And iPad Are Revolutionary Products Whose

Success Is Built On Their Unique Design And User Experience

When Apple unveiled the iPhone on January 9, 2007, it was unlike any other

smartphone on the market. The iPhone's unique design and user interface were the

result of years of research and development within Apple. A20484-20485(484:24-

485:4); A20750-20751(750:25-751:11). Those attributes of the iPhone received

-5-

immediate critical acclaim. E.g., A32717-32718 (New York Times describing the

iPhone as "gorgeous" with a "shiny black [front face], rimmed by mirror-finish

stainless steel" and a "spectacular and practical" user interface); A32721 (Wall

Street Journal describing the iPhone as "a beautiful and breakthrough handheld

computer," featuring a "clever finger-touch interface"); A32726-32727 (Time

Magazine naming the iPhone "Invention of the Year" and listing the iPhone's

"pretty" design and "whole new kind of [user] interface" as the top two reasons for

the award). The iPhone's unique design and user interface brought Apple huge

success in the smartphone market. A20625-20626(625:1-626:4).

Three years later, Apple's release of the iPad was equally revolutionary--

creating an entire market for tablet computers that others had previously

abandoned as "a dead category and not likely to succeed." A20620-20621(620:12-

621:10). As with the iPhone, the iPad was immediately praised for its

groundbreaking user interface. A32734-32735 (USA Today describing the iPad as

"fun" and "simple" with a touch-controlled user interface that allows users to

"pinch to zoom in or out"); A32737 (Wall Street Journal describing the iPad as a

"beautiful new touch-screen device" with a "finger-driven multitouch user

interface" that could displace "the mouse-driven interface that has prevailed for

decades"). Again, the iPad's easy-to-use interface was critical to its instant

commercial success. A20626(626:7-19).

-6-

1. Apple's design patents and iPhone trade dress

Apple sought and obtained numerous patents to protect its investment in the

innovative designs and functionalities of the iPhone and iPad. The iPhone design

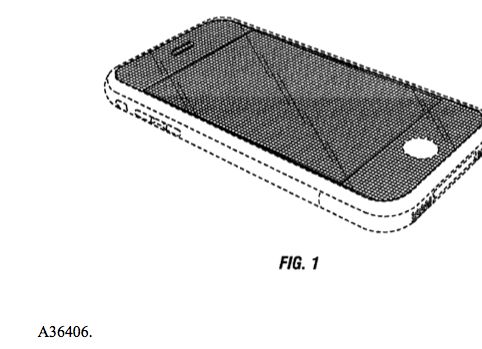

is protected by, among others, U.S. Design Patent Nos. 618,677 ("D'677 patent"),

593,087 ("D'087 patent"), and 604,305 ("D'305 patent").

The D'677 patent claims the distinctive front face of the iPhone, including

its shape, rounded corners, black color, and reflective surface:

-7-

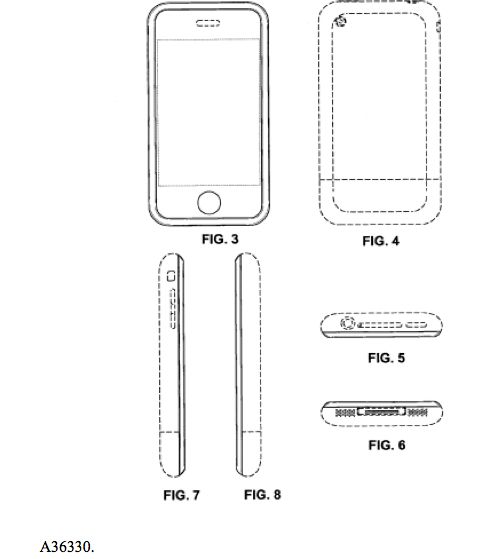

The D'087 patent claims the iPhone's overall distinctive appearance,

including the bezel from the front of the phone to the sides and flat contour of the

front face:

-8-

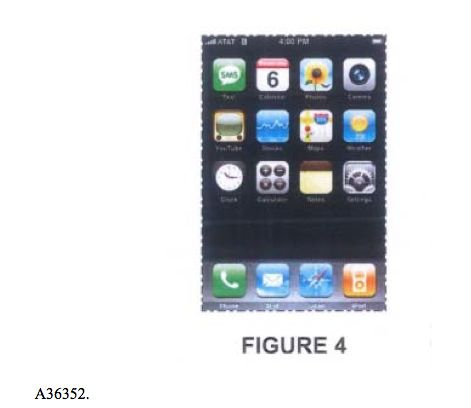

The D'305 patent claims the ornamental design of the iPhone's unique

graphical user interface, including the arrangement of rows of colorful square icons

with rounded corners:

The distinctive design of the front face of the iPhone is further protected by

Apple's registered and unregistered iPhone trade dress. Apple's iPhone trade dress

protects the overall visual impression of the non-functional elements of the

iPhone's front face, including: (i) a rectangular product with four evenly rounded

corners; (ii) a flat, clear surface covering the front of the product; (iii) a display

screen under the clear surface; (iv) substantial black borders above and below the

-9-

display screen and narrower black borders on either side of the screen; (v) when

the device is on, a row of small dots on the display screen; (vi) when the device is

on, a matrix of colorful square icons with evenly rounded corners within the

display screen; and (vii) when the device is on, a bottom dock of colorful square

icons with evenly rounded corners set off from the other icons on the display,

which does not change as other pages of the user interface are viewed. A20339-

20340(339:21-340:12); A21091-21092(1091:11-1092:23); see also A50104.

2. Apple's utility patents

Along with those protections for the iPhone's design, Apple has numerous

utility patents covering various functions of the unique user experience for the

iPhone and iPad. Among those patents are U.S. Patent Nos. 7,469,381 ("'381

patent"), 7,844,915 ("'915 patent"), and 7,864,163 ("'163 patent").

The '381 patent claims the "bounce-back" feature used by the iPhone and

iPad: when a user of a touchscreen device scrolls beyond the edge of an electronic

document, the device causes the electronic document to bounce back so that no

space beyond the edge of the document is displayed. A36502-36505; A36519-

36520; see also A21736-21739(1736:16-1739:21).

The '915 patent claims the multi-touch display functionality of the iPhone

and iPad, which allows those products to distinguish between single-touch

commands for scrolling through documents and multi-touch gestures to manipulate

-10-

a document (e.g., a two-fingered "pinch-to-zoom" gesture). A36448; A36459; see

also A21817-21818(1817:8-1818:22).

The '163 patent claims the "double-tap-to-zoom" capability of the iPhone

and iPad, which allows a touchscreen device to enlarge and center the text of an

electronic document when a user taps twice on a portion of that document and, in

response to a second user gesture on another portion of the document, recenters the

screen over that portion of the document. A36564; A36568; A36570; see also

A21831-21832(1831:9-1832:21).

*****

Because they protect key designs and functionalities that have fueled the

iPhone's and iPad's overwhelming success, the D'677, D'087, D'305, '381, '915,

and '163 patents as well as Apple's iPhone trade dress are crown jewels of Apple's

"unique user experience" IP portfolio. A21954-21957(1954:19-1957:9); A21963-

21964(1963:23-1964:8); A22010(2010:3-17); A22012(2012:6-16). Apple has only

rarely agreed to license its utility patents falling within this category to other

companies, has agreed to license its design patents even more rarely, and has never

licensed its trade dress. The few instances in which Apple has licensed its patents

covering Apple's unique user experience have occurred under circumstances that

would not "enabl[e] somebody to build a clone product" of the iPhone or iPad.

A21956-21957(1956:21-1957:9); see also A22010-22012(2010:6-2012:16)

-11-

(describing Apple's use of "anti-cloning" provisions in licenses to its unique user

experience patents); A4075-4076(¶¶3-7) (describing unique circumstances of and

restrictions contained in Apple's licenses to IBM and Nokia).

B. Samsung Deliberately Copied Apple's iPhone And iPad To

Compete Directly With Apple

Samsung and Apple compete fiercely for U.S. smartphone customers. But

Samsung has chosen to compete not through innovation, but through calculated

and meticulous copying of Apple's popular iPhone and iPad. After the iPhone

took the market by storm in 2007, Samsung faced, as its executives lamented, "a

crisis of design." A30874. The explosive success of the iPhone re-shaped

consumer expectations and convinced Samsung's executives that "when our [user

interface] is compared to the unexpected competitor Apple's iPhone, the difference

is truly that of Heaven and Earth." Id. As the president of Samsung's mobile

division explained, Samsung resolved to "make something like the iPhone" to

remain competitive in the smartphone market. A30871.

-12-

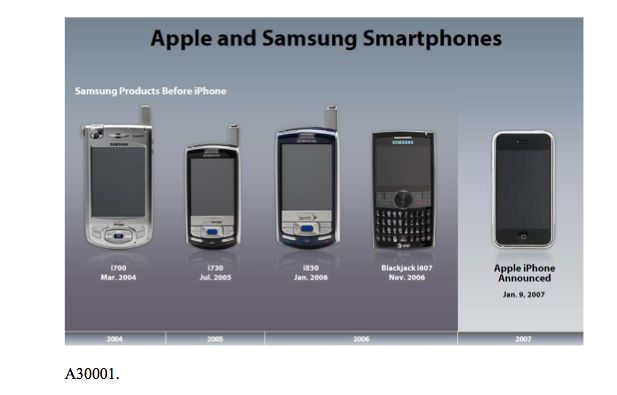

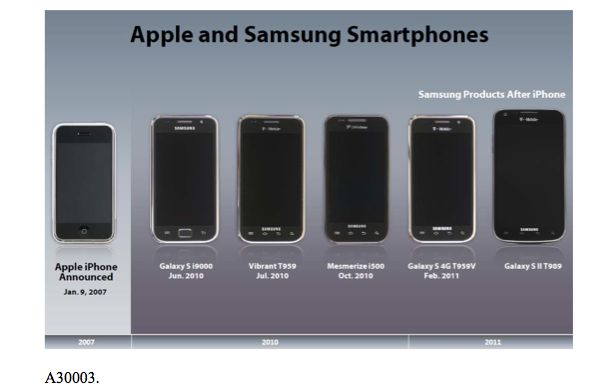

The transformation in Samsung's products after the iPhone's introduction

shows the results of those efforts. Before the iPhone's introduction, Samsung's

phones and the iPhone differed markedly in their shape, button configuration, and

role of the screen in the overall front of the phone:

-13-

After the iPhone's success, Samsung's phones became iPhone clones:

Samsung's copying was not limited to the iPhone's external appearance.

Samsung also copied Apple's innovative user interface, including the "bounce-back," "pinch-to-zoom," and "double-tap-to-zoom" features covered by Apple's

'381, '915, and '163 patents. Samsung's documents show that this copying was no

accident. Rather, Samsung carefully compared its smartphones and tablets to the

iPhone and iPad so that it could identify and copy the features that Samsung's

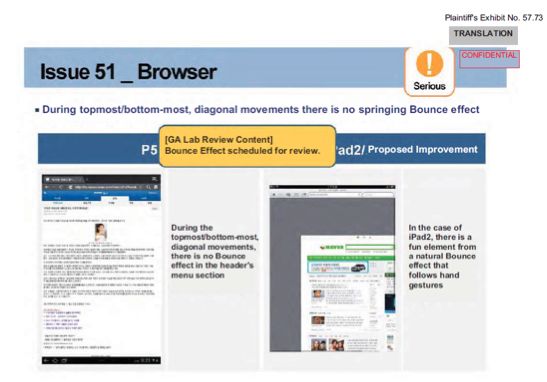

products lacked. For example, Samsung concluded from its side-by-side

-14-

comparison that the absence of Apple's "bounce" feature was a "serious" defect

that needed to be added to Samsung's smartphones and tablets:

A31603 (Samsung internal comparison of its Galaxy tablet computer with the iPad

2); A31549 (identifying Samsung's lack of a "bounce effect" in its products as a

"critical" defect); see also> A21763-21764(1763:16-1767:6).

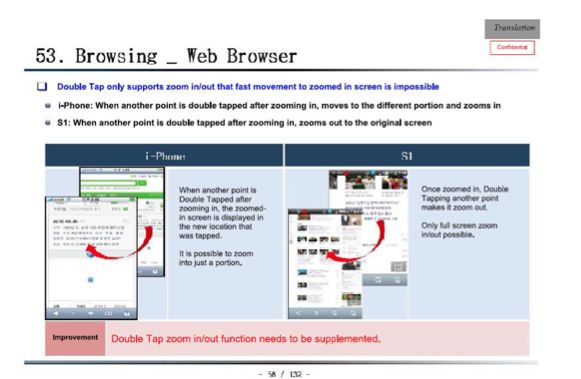

Likewise, Samsung chose to "[a]dopt [d]ouble-[t]ap as a supplementary

zooming method," using the iPhone as a "design benchmark." A30868. Again,

Samsung's implementation of that feature was based on a side-by-side comparison

-15-

with the iPhone with suggested "[i]mprovement[s]" for making Samsung's

products function more like Apple's:

A30948 (Samsung internal comparison of its Galaxy S1 smartphone with the

iPhone); see also A20827-20828(827:3-828:17).

Samsung similarly implemented Apple's "pinch-to-zoom" feature after its

consultants reported that the iPhone's use of that feature allows "more intuitive and

easier browsing" (A4493) and that consumers complained that "the zoom on web

pages and ability to scroll around is very bad and hard to do" on Samsung's prior

phones (A4489).

-16-

C. Through Its Infringement And Dilution, Samsung Took

Significant Market Share From Apple

Samsung's strategy was highly successful. By copying Apple's protected

designs and patented features, Samsung undercut Apple's pricing to "directly go

after ... potential iPhone purchasers." A31976.2

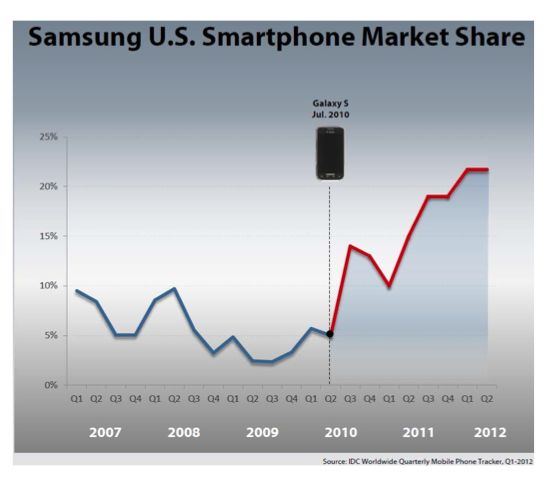

Samsung captured market share from Apple that Samsung's older, non-cloned products were never able to achieve. Before launching its initial infringing

and diluting Galaxy S product line in July 2010, Samsung was losing market share.

A22043-22044(2043:18-2044:23). After launching its infringing and diluting

products, however, Samsung's market share jumped. A22044(2044:20-23)

("Samsung's market share took an abrupt upward swing and has continued today

to advance dramatically in increases in market share."). Indeed, Samsung's launch

of its infringing and diluting products marked a key inflection point in Samsung's

share of the smartphone market, the beginning of a jump from 5% to 20% of the

market in just two years:

-17-

A50105; see also A22043(2043:18-2045:10). By the second quarter of 2012,

Samsung's U.S. smartphone market share had increased further still to over 30%.

A4984(¶25); A4993.

Samsung's significant market growth through its infringing and diluting

products came directly at Apple's expense, as the district court found (A5) and

Samsung's own documents confirm (e.g., A31903 (graph showing Apple's market

share decrease in late 2011 while Samsung's market share grew)). Samsung's

-18-

success in capturing market share from Apple led Samsung to conclude that the

U.S. smartphone market is becoming a "two horse race between Apple and

Samsung." A31903.

In addition to increasing Samsung's market share, Samsung's infringement

and dilution yielded enormous profits for Samsung. Trading on the success of the

iPhone and iPad, sales of Samsung's infringing and diluting smartphones generated

over $7.2 billion in revenue and $2 billion in gross profits. See A40944 (revenues

for accused products); A30475 (profits for accused products); A4186-4196 (verdict

identifying infringing and diluting products).

D. Apple Lost Substantial Downstream Sales Due To Samsung's

Infringement And Dilution

While Samsung's infringing and diluting products caused Apple to lose

smartphone and tablet sales, that is only the beginning of the harm to Apple, as the

district court correctly concluded. A5-6. Customers who purchase an iPhone or

iPad are likely to buy other Apple products and services, including related

products, applications, accessories, and future smartphones and tablets. A20615-

20617(615:14-617:6). Those lost downstream sales extend even beyond the

individual purchaser: the smartphone market is influenced by "network effects,"

meaning that individuals are more likely to buy a particular smartphone if many

others have bought it as well. A20617(617:3-6) (describing how one's smartphone

-19-

purchases directly influence purchases made by "the other people around you, who

you work with or in your family").

Samsung itself has recognized the loyalty (or "stickiness") of smartphone

buyers, such that an initial purchase promotes future sales, and tailored its

marketing strategies to capture those downstream sales. A31913 (Samsung

strategy document describing Apple customers as "very sticky/loyal subscribers").

As Samsung's head of sales and marketing for its mobile division confirmed,

Samsung tries "to get first-time smartphone users before they're locked into the

[Apple] IOS so that Samsung can lock them into the Android [operating system]."

A4070-4071(71:22-72:19).

E. Design And Ease Of Use Are Important To Smartphone

Purchasers

The motivation behind Samsung's decision to copy the iPhone was clear:

Samsung recognized the undeniable importance of design and user interface to

smartphone purchasers. Samsung's and its consultants' market research--based

on interviews of thousands of consumers and dozens of industry experts--

identified those factors as the two key reasons for the iPhone's extraordinary

success. A30528 (identifying "[e]asy and intuitive user interface" and "[b]eautiful

design" as the top two "Factors that Could Make iPhone a Success"); A30680

(identifying "[e]ase of use" as "the major driver" of consumer interest in

touchscreen devices); A30698 (iPhone's "strong, screen-centric design has come to

-20-

equal what's on trend and cool for many consumers"); A4969 (recognizing that

U.S. consumers "have been greatly influenced by the iPhone design," which is

considered "premium"); A4280 ("the iPhone is a delight to the eye" and "the most

inspired mobile handset on the market"). Not surprisingly, Samsung's own

surveys showed that those same factors drove demand for Samsung's infringing

smartphones. Indeed, as the district court observed, Apple presented "significant

evidence" that design is "important in consumer choice," including a "Samsung

study finding exterior design to be an important factor in phone choice." A8; see

also A32004 (March 2011 J.D. Power survey concluding that "[n]early half (45%)

of smartphone owners indicate they chose their model because they liked its

overall design and style .... Simple operation is important, as 36% of owners

report having chosen their handset because it is `generally easy to use.'"); A32050

(same).

For its part, Apple also recognized the importance of design and user

interface to smartphone purchasers, and specifically to Apple's customers. E.g.,

A32770 (Apple customer survey showing that 95% of U.S. respondents considered

"easy to use" to be "very important" or "somewhat important" to their decision to

purchase an iPhone); A50102 (summary of Apple customer survey data showing

that over 80% of respondents considered "attractive appearance and design" to be

-21-

"very important" or "somewhat important" in their decision to purchase an

iPhone).

The touchscreen features claimed by Apple's asserted utility patents are

likewise important to driving consumer demand. Testimony, surveys, and other

documents referred to Apple's "multi-touch experience that makes the iPhone easy

to use" as "a key driver of demand for the iPhone." A4503-4511(509:7-517:8); see

also A4500-4502(487:6-489:15) (describing how Apple's multi-touch user

interface "is probably among the most important of all the elements of how

customers perceive ease of use on an iPhone"); A30677-30683 (Samsung survey

evidence concerning importance of touchscreen capabilities to consumer

purchasing decisions); A32719 (New York Times review praising multi-touch

features of the iPhone); A32723 (Wall Street Journal describing the iPhone's

multi-touch features as "effective, practical and fun"); A32727 (Time Magazine

listing the iPhone's multi-touch features among the top reasons for naming the

iPhone "Invention of the Year"). Moreover, consumer survey evidence

specifically targeted to the three asserted utility patents showed that Samsung

consumers were willing to pay statistically significant price premiums for the

features protected by Apple's patents. A30488 (survey results showing that

consumers are willing to pay $39 more for a smartphone and $45 more for a tablet

computer that includes Apple's patented "pinch-to-zoom" feature and $100 more

-22-

for a smartphone and $90 for a tablet computer that includes all three features

claimed by Apple's asserted utility patents); see also A21915-21916(1915:7-1916:13).

Samsung's copying altered consumer perceptions of Samsung's products.

Consumers previously considered Samsung's design and user interface to be

inferior to Apple's (A4958-4959), found Internet browsing on Samsung's phones

to be "so painful as to be not worth it" (A4488), and did not view Samsung as a

"credible" smartphone manufacturer (A4487). But after Samsung implemented

Apple's protected designs and patented features, consumers ranked Samsung's

infringing smartphones (such as the Galaxy S "Vibrant") as comparable to the

iPhone. E.g., A32077 (collecting consumer satisfaction survey results).

F. The District Court's Decision

After the jury confirmed Samsung's infringement and dilution, Apple sought

a permanent injunction because (among other reasons) Samsung's actions were

irreparably harming Apple in a way that money damages could not cure.

The district court made numerous findings that support entry of an

injunction. The court found "that Apple and Samsung are direct competitors ... for

first-time smartphone buyers" and "that Apple and Samsung continue to compete

directly in the same market," which "increases the likelihood of harm from

continued infringement." A5. The court noted that it was undisputed that

-23-

"Samsung's market share grew substantially from June 2010 through the second

quarter of 2012" and "that Samsung had an explicit strategy to increase its market

share at Apple's expense." Id. Based on that evidence, the district court

determined that "Apple has continued to lose market share to Samsung," which

"can support a finding of irreparable harm." Id.

The district court also concluded that initial lost sales to Samsung could

result in "lost future sales of both future phone models and tag-along products like

apps, desktop computers, laptops, and iPods," which "Samsung ... made no

attempt to refute." A6. As a result, the court found "that Apple has suffered some

irreparable harm in the form of loss of downstream sales." Id.; see also A16

("[T]he Court agrees that Apple has likely suffered, and will continue to suffer, the

loss of some downstream sales."). The court also recognized that the difficulty in

calculating Apple's lost downstream sales suggested the inadequacy of money

damages. A16 ("Apple's evidence of lost downstream sales does provide some

evidence that Apple may not be fully compensated by the damages award.").

Nevertheless, the district court concluded that money damages were

adequate compensation because Apple had not demonstrated that its patents are

"priceless" or "off limits" to licensing. A17. The court relied heavily on Apple's

past offer to license some unasserted patents to Samsung and licenses to the

-24-

asserted utility patents to other companies (IBM, Nokia, and HTC) made in the

context of broad cross-licensing agreements or litigation settlements. A17-18.

The district court rejected Samsung's argument concerning the balance of

hardships because Samsung claimed to have stopped making twenty-three of the

infringing products and to have developed design-arounds for the other infringing

products. A18-19. As the court explained, Samsung "cannot now turn around and

claim that [it] will be burdened by an injunction that prevents sale of these same

products." A19. The court nonetheless determined that "neither party would be

greatly harmed by either outcome" and considered the balance of hardships a

"neutral" factor. A18-19.

Regarding the public interest, the district court recognized that "the public

interest does favor the enforcement of patent rights to promote the `encouragement

of investment-based risk.'" A20 (quoting Sanofi-Synthelabo v. Apotex, Inc., 470

F.3d 1368, 1383 (Fed. Cir. 2006)). Ultimately, however, the court determined that

the patented designs and features were small components of the infringing products

such that "it would not be in the public interest to deprive consumers of phones

that infringe limited non-core features." A21.

Despite Apple's strong showing of irreparable harm (and, indeed, the district

court's own finding that Apple had already suffered irreparable harm), the court

denied Apple's request for an injunction. The court's "first and most important[]"

-25-

reason (A21) for reaching that result was its view that Apple had not satisfied the

"causal nexus" requirement this Court established for preliminary injunctions in

Apple, Inc. v. Samsung Electronics Co., 678 F.3d 1314 (Fed. Cir. 2012) ("Apple

I"), and Apple Inc. v. Samsung Electronics Co., 695 F.3d 1370, 1374 (Fed. Cir.

2012) ("Apple II"). With little analysis, the district court held that the same causal

nexus requirement applies with equal force to permanent injunctions. A3 n.2. The

court then ruled that, to support a permanent injunction, Apple was required to

show that each of the infringing features "drives consumer demand" for the

infringing devices or, in other words, that "consumers buy the infringing product

specifically because it is equipped with the patented feature." A8 (first emphasis

added).

With respect to Samsung's continued dilution of Apple's trade dress, the

district court found that Apple would not be irreparably harmed absent an

injunction because "none of the [diluting] Samsung products ... are still on the

market" (A15), even though the court had earlier recognized that "Samsung's

decision to cease selling its infringing phones does not alter the Court's irreparable

harm analysis." A7; see also id. ("Absent an injunction, Samsung could begin

again to sell infringing products, further exposing Apple to the harms identified

above.").

-26-

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

The four traditional equitable factors for injunctive relief overwhelmingly

favor entry of a permanent injunction against Samsung's continued infringement.

Based largely on undisputed evidence, the district court concluded that: (1) Apple

and Samsung are direct competitors, which "increases the likelihood of harm from

continued infringement" (A5); (2) Samsung continues to cause irreparable harm to

Apple through lost market share and lost downstream sales (A5-6), which

"support[s] a finding that monetary damages would be insufficient to compensate

Apple" (A16 (quoting Apple I, 678 F.3d at 1337)); (3) the balance of hardships is

at worst a "neutral" factor (A19); and (4) "the public interest does favor the

enforcement of patent rights" (A20). The court's ruling that monetary damages

would sufficiently compensate Apple was based on the belief that Apple did not

view its patents as "priceless" or "off limits" (A17)--a legally erroneous standard

that this Court has never required--and a misunderstanding of the licensing

evidence, which makes clear that Apple would never license the patents protecting

Apple's unique user experience to its primary competitor. Accordingly, under the

governing eBay test, an injunction should have issued.

The district court further erred by also requiring Apple to prove that each of

the patented features independently drives consumer demand for the infringing

products. A7-12. Neither the Supreme Court nor this Court has ever required a

-27-

patentee to satisfy this additional "causal nexus" requirement at the permanent

injunction stage--after the defendant's infringement has already been adjudicated.

Moreover, the district court's rigid application of the causal nexus requirement--

requiring evidence "not just that there is demand for the patented features, but that

the patented features are important drivers of consumer demand for the infringing

products" (A12)--will all but foreclose the possibility of injunctive relief in cases

that, like this one, involve infringement by complex, multi-featured products. The

district court's reliance on the causal nexus requirement to defeat a strong showing

on the eBay factors conflicts with principles of equity, which traditionally reject

bright-line rules "suggesting that injunctive relief could not issue in a broad swath

of cases." eBay, 547 U.S. at 393. To the extent that any causal nexus requirement

applies at the permanent injunction stage, Apple presented more than sufficient

evidence that its patented designs and features influence consumer demand such

that Apple's irreparable harm can be attributed to Samsung's infringement.

The district court also abused its discretion in denying Apple an injunction

against Samsung's trade dress dilution. The court committed legal error in

concluding that Samsung's statements that it had voluntarily ceased its diluting

activities defeated Apple's right to injunctive relief. A15. Similarly, the court's

conclusion that monetary damages would be adequate compensation for any future

dilution rested on clearly erroneous factual findings. A17.

-28-

Because it would be an abuse of discretion not to enter a permanent

injunction on this record, Apple respectfully requests that this Court reverse the

district court's denial of Apple's motion for a permanent injunction against

Samsung's continued infringement and dilution. At the very least, vacatur and

remand is warranted so that the district court may consider the matter under the

proper legal standard and with a correct understanding of the record.

STANDARD OF REVIEW

This Court reviews the denial of a permanent injunction for abuse of

discretion. Bosch, 659 F.3d at 1147. "A district court abuses its discretion when it

acts `based upon an error of law or clearly erroneous factual findings' or commits

`a clear error of judgment.'" Id. (quoting Ecolab, Inc. v. FMC Corp., 569 F.3d

1335, 1352 (Fed. Cir. 2009)).

ARGUMENT

As the district court's own findings confirm, Apple presented a classic case

for injunctive relief, involving direct competitors and undisputed evidence of

irreparable harm, including lost market share and lost downstream sales that

money damages cannot fully compensate. The district court nevertheless applied a

rigid causal nexus requirement to defeat Apple's strong showing on the four eBay

factors. As explained below, that was error because neither the Supreme Court nor

this Court has ever required evidence of a causal nexus at the permanent injunction

-29-

stage after a finding of infringement, let alone the highly particularized showing

that the district court demanded here.

The inconsistency between eBay and this Court's permanent injunction cases

on the one hand and the causal nexus requirement applied by the district court on

the other becomes most salient in view of the findings the district court actually

made. Those findings--mostly based on undisputed evidence--strongly support

entry of a permanent injunction against a direct competitor's adjudicated

infringement. The district court's application of the causal nexus requirement to

bar permanent injunctive relief--regardless of the strength of the patentee's

showing under the traditional eBay factors--is unprecedented and legally

erroneous. This Court should therefore reverse the district court's order denying

Apple's motion for a permanent injunction.

I. THE EQUITIES STRONGLY FAVOR GRANTING INJUNCTIVE RELIEF TO BAR

FURTHER PATENT INFRINGEMENT BY A DIRECT COMPETITOR

The evidence presented at trial and through post-trial briefing

overwhelmingly favors entry of a permanent injunction to protect Apple from

further irreparable harm caused by Samsung's deliberate and successful strategy of

acquiring customers by copying Apple's products. The district court made a series

of findings suggesting--or even outright concluding--that each equitable factor

under eBay favors entry of a permanent injunction. E.g., A6 ("[T]he Court finds

that Apple has suffered some irreparable harm in the form of loss of downstream

-30-

sales."); A16 ("The Federal Circuit has confirmed that `the loss of customers and

the loss of future downstream purchases are difficult to quantify, [and] these

considerations support a finding that monetary damages would be insufficient to

compensate Apple.'" (quoting Apple I, 678 F.3d at 1337)); A19 (rejecting

Samsung's argument concerning balance of hardships because Samsung claims to

have ceased selling infringing and diluting products and "cannot now turn around

and claim that [it] will be burdened by an injunction that prevents sale of these

same products"); A20 ("As this Court found at the preliminary injunction stage, the

public interest does favor the enforcement of patent rights to promote the

`encouragement of investment-based risk.'" (quoting Sanofi-Synthelabo, 470 F.3d

at 1383)).

In light of those findings, the district court's decision to deny an injunction

cannot be reconciled with this Court's post-eBay permanent injunction cases,

which confirm that permanent injunctive relief should be granted in cases of head-

to-head competition involving lost market share. E.g., Bosch, 659 F.3d at 1150-1151 (concluding that permanent injunction should issue against direct competitor

whose continued infringement caused plaintiff-patentee to lose significant market

share); Acumed LLC v. Stryker Corp., 551 F.3d 1323, 1327-1329 (Fed. Cir. 2008)

(same); Verizon Servs. Corp. v. Vonage Holdings Corp., 503 F.3d 1295, 1310-

1311 (Fed. Cir. 2007) (same); see also Presidio Components, Inc. v. Am. Technical

-31-

Ceramics Corp., 702 F.3d 1351, 1363 (Fed. Cir. 2012) (vacating denial of

permanent injunction due to evidence of "direct and substantial competition

between the parties" and lost sales). Had the district court properly applied eBay,

it would have reached the same conclusion in this case.

A. Apple Is Being Irreparably Harmed By The Threat Of Its Direct

Competitor's Continued Infringement

1. Apple and Samsung compete directly for first-time

smartphone buyers

The district court correctly found that Apple and Samsung are direct

competitors in the market for first-time smartphone buyers. A5 ("[T]he Court

finds that Apple and Samsung continue to compete directly in the same market.").

The court made that finding earlier in the case when considering Apple's motion

for a preliminary injunction (A4114-4115), and "Samsung ... presented no new

evidence to refute that finding" (A5). In fact, this very case arose because of

Samsung's desire to compete (unfairly) with Apple by copying Apple's patented

product designs and features. See supra pp. 12-16.

The direct competition between Apple and Samsung is strong evidence of

irreparable harm to Apple, as the district court recognized. A5 (citing Bosch, 659

F.3d at 1153). If the U.S. smartphone market is truly becoming a "two horse race

between Apple and Samsung," as Samsung admits (A31903), then the harm to

Apple from Samsung's continued infringement is particularly severe, because sales

-32-

lost to Samsung presumably would have otherwise gone to Apple. See Bosch, 659

F.3d at 1151. That is just what Samsung intended, and Samsung should not be

allowed to continue with its strategy after having been adjudicated to infringe

Apple's patents.

2. Apple has lost market share due to its direct competitor's

adjudicated infringement

As the district court concluded and Samsung did not dispute, "Samsung had

an explicit strategy to increase its market share at Apple's expense" through its

deliberate copying of Apple's patented designs and product features. A5. That

strategy was wildly successful and irreparably harmed Apple's competitive

standing. Samsung was losing market share before it started selling its infringing

products in the United States in June 2010. A22043-22044(2043:18-2044:23).

But after launching those products, Samsung's market share grew--and grew

rapidly--increasing from 5% in June 2010 to over 30% by the second quarter of

2012. A4984(¶25); A4993; see also supra p. 18 (reproducing graph showing

Samsung's growth in market share since launching its infringing smartphones

(A50105)).

Samsung's rapid growth in market share undeniably came at Apple's

expense, as the district court correctly found. A5 ("Thus, the cumulative evidence

shows that, consistent with the Court's finding at the preliminary injunction phase,

Apple has continued to lose market share to Samsung."). Indeed, Samsung's own

-33-

documents confirm that Samsung has been taking market share from Apple.

A31903.

Although the overall effect of Apple's lost market share is difficult to

quantify with precision, it is undoubtedly substantial. Sales of Samsung's

infringing and diluting products generated over $7.2 billion in revenue and

$2 billion in gross profits. See A40944; A30475; A4186-4196. Apple is unlikely

to recoup much of that market share because, as Samsung's own witnesses

confirmed, consumers are reluctant to switch between competing smartphone

platforms once they have been "locked into" their initial purchase. A4070-

4071(71:22-72:19) (describing Samsung's strategy "to get first-time smartphone

users before they're locked into the [Apple] IOS so that Samsung can lock them

into the Android [operating system]").

Such evidence of lost market share "squarely supports a finding of

irreparable harm." Presidio, 702 F.3d at 1363; see also Merial Ltd. v. Cipla Ltd.,

681 F.3d 1283, 1307 (Fed. Cir. 2012); Bosch, 659 F.3d at 1151; Acumed, 551 F.3d

at 1329. Indeed, the district court itself recognized that lost market share is

evidence of irreparable harm. A5.

3. Apple has lost downstream sales due to its direct

competitor's adjudicated infringement

As the district court found, Apple's initial lost sales due to Samsung's

infringement cause further downstream lost sales for related products, apps,

-34-

accessories, and future smartphone purchases. A5-6. Apple's lost downstream

sales extend even beyond the individual customer who decides initially to buy a

Samsung product instead of an iPhone or iPad. As the district court acknowledged

when ruling on Apple's motion for a preliminary injunction in Apple II, "network

effects help shape the smartphone market," such that "customer demand for a

given smartphone platform increases as the number of other users on the platform

increases." A50076; see also A20617(617:3-6) (trial testimony that smartphone

sales can influence the purchasing decisions of "the other people around you, who

you work with or in your family").

Given the particular difficulty in ascertaining the full extent of the harm

from lost downstream sales, this Court has consistently recognized that lost

downstream sales demonstrate irreparable harm. See Verizon, 503 F.3d at 1310

(recognizing "lost opportunities to sell other services to the lost customers" as a

form of irreparable harm); see also Broadcom Corp. v. Qualcomm Inc., 543 F.3d

683, 702-703 (Fed. Cir. 2008) (competition for "design wins" that influence future

product development supports a finding of irreparable harm, even where the

patentee and adjudged infringer did not compete for sales on a unit-by-unit basis).

The district court thus correctly found that "Apple has suffered some irreparable

harm in the form of loss of downstream sales." A6.

-35-

B. Money Damages Are Inadequate To Remedy Apple's Loss Of

Market Share And Downstream Sales To Its Direct Competitor

Apple's loss of market share and downstream sales are precisely the type of

damages that cannot be calculated to a reasonable certainty and cannot be fully

compensated with a monetary award, as the district court itself recognized. A18

("[T]he difficulty in calculating the cost of lost downstream sales does suggest that

money damages may not provide a full compensation for every element of Apple's

loss."); see also Broadcom, 543 F.3d at 703-704 ("[D]ifficulty in estimating

monetary damages reinforces the inadequacy of a remedy at law."); i4i Ltd. P'ship

v. Microsoft Corp., 598 F.3d 831, 862 (Fed. Cir. 2010) (concluding that money

damages could not remedy "loss of market share, brand recognition, and customer

goodwill" because "[s]uch losses may frequently defy attempts at valuation");

Acumed, 551 F.3d at 1328 (affirming grant of permanent injunction where patentee

had shown lost market share causing irreparable injury).

Nevertheless, the district court concluded that Apple's past licenses of

certain utility patents and Samsung's ability to pay a judgment showed the

adequacy of money damages. A17-18. That conclusion was erroneous in several

respects.

First, the district court set an impossibly stringent--and legally incorrect--

standard with respect to Apple's past licensing practices, requiring Apple to show

that its patents are "priceless" or wholly "off limits" such that "no fair price" could

-36-

be set for a license in order to demonstrate the inadequacy of money damages.

A17. But regardless of whether Apple's patents are deemed "priceless" or "off

limits," money damages are inadequate due to the difficulty of quantifying

damages attributable to Apple's lost market share and downstream sales. See

Apple I, 678 F.3d at 1337. Indeed, after eBay, this Court has found money

damages adequate only where the patentee--unlike Apple--failed to prove that

damages would be difficult to calculate. See ActiveVideo Networks, Inc. v. Verizon

Commc'ns, Inc., 694 F.3d 1312, 1340 (Fed. Cir. 2012); Voda v. Cordis Corp., 536

F.3d 1311, 1329 (Fed. Cir. 2008).

Second, the district court's analysis is contrary to eBay, where the Supreme

Court explicitly rejected a rule that a patentee's willingness to license its patents

suffices by itself to demonstrate a lack of irreparable harm. 547 U.S. at 393

(explaining that patentees that license, but do not practice, their patents can

nonetheless prove irreparable harm under certain circumstances); see also Acumed,

551 F.3d at 1328 ("A plaintiff's past willingness to license its patent is not

sufficient per se to establish lack of irreparable harm if a new infringer were

licensed."); Broadcom, 543 F.3d at 703 (rejecting argument that prior license

demonstrated adequacy of money damages). Yet in concluding that money

damages were adequate, the district court identified only a single factor aside from

Apple's supposed willingness to license: Samsung's ability to pay a money

-37-

damages award. A18. But unlike a defendant's inability to pay money damages--

which may demonstrate the inadequacy of money damages--the ability to pay

damages has little significance. Indeed, with a steady stream of income from its

continued infringement, a defendant's ability to pay is readily demonstrated in

most cases.

Third, the district court clearly erred in finding that Apple's past licensing

practices suggest Apple's willingness to license the patents-in-suit to Samsung.

Boris Teksler, Apple's director of patents and licensing, testified that Apple never

offered to license the patents-in-suit to Samsung and that Apple was "very clear"

that any license would exclude those patents as "untouchables" that are part of

Apple's "unique user experience." A22013-22014(2013:9-2014:6);

A22022(2022:22-24). The district court cited no contrary evidence, finding only

that Apple had offered to license "some ... patents," not any of the patents-in-suit,

to Samsung. A17. The district court likewise misinterpreted Mr. Teksler's

testimony that Apple had "over time" licensed patents covering its unique user

experience as suggesting Apple's willingness to license those rights more generally

to its competitors. A17. What Mr. Teksler actually said when asked whether

Apple had "ever licensed any of the patents within this category" is:

Certainly over time we have, but I can count those instances on one

hand quite easily. And we do so with rare exception and we do it

consciously knowing that we're not enabling somebody to build a

clone product.

-38-

A21957(1957:3-9). The unrestricted compulsory license to Apple's patents that

Samsung would enjoy absent an injunction is entirely inconsistent with Apple's

"rare" and limited licensing practice for patents covering its unique user

experience.

Nor was the district court correct to conclude that licenses of certain Apple

utility patents to IBM, Nokia, and HTC suggested Apple's willingness to license

its asserted patents to Samsung for use in competing products. Those agreements

provide no basis for concluding that Apple would ever be willing to license its

design patents to Samsung. Indeed, Apple's licenses to IBM, Nokia, and HTC do

not even include any such design patents. A4308(¶1.10) (Nokia license limiting

"Licensed Apple Patents" to certain specific utility patents and patents essential to

comply with industry standards); A4443 (IBM license excluding all Apple design

patents except for fonts); A4783(¶1.11) (HTC license excluding Apple's design

patents from "Covered Patents").

The IBM, Nokia, and HTC licenses also do not suggest any willingness on

Apple's part to license its asserted utility patents--without restriction--to a direct

competitor like Samsung. In concluding otherwise, the district court failed to

consider the unique context of the prior agreements, as it was required to do. See

O2 Micro Int'l Ltd. v. Beyond Innovation Tech. Co., No. 2011-1054, 2011 WL

5601460, at *9 (Fed. Cir. Nov. 18, 2011) (nonprecedential) (explaining that "the

-39-